Most of us have done it at some time—when given negative feedback we become defensive and find excuses for the actions that are being criticised, or we turn it around and criticise those who are criticising us. Criticism is never easy to take. It’s an understandable reaction, and one that is just as common in organisations as it is in individuals.

A decade or so ago I was working for a large unitary authority when its first Comprehensive Performance Assessment (CPA) results were announced. They had been rated as ‘weak’—the second lowest of five possible ratings. Rather than acknowledge the failings and focus on how to improve, the initial response of the the Leader of the Council was to brand the decision as unfair and criticise the Audit Commission’s approach to assessment1.

More recently, the Francis Inquiry into the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust noted that the Trust has failed to take notice of multiple warning signs and found a culture of defensiveness, inward looking and lack of openness to criticism to be major contributors to the extensive problems there. The report observes:

The Trust’s culture was one of self promotion rather than critical analysis and openness… It took false assurance from good news, and yet tolerated or sought to explain away bad news (para 1.7)2

and continues:

…the Trust was an organisation that lacked insight and awareness of the reality of the care being provided to patients. It was generally defensive in its reaction to criticism and lacked openness with patients, the public and external agencies (para 1.114)3

Denying criticism may not always lead to the atrocious failures that happened in Mid Staffordshire, where some reports estimate up to 1,200 patients may have died as a result4, but it is surely not the action of an organisation focused on learning and continual improvement.

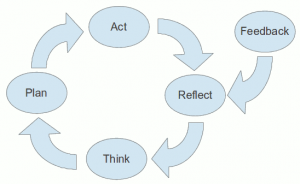

Feedback informing Kolb’s cycle of learning

(adapted from Kolb5)

Feedback is a vital part of learning, whether that be for individuals or organisations. It illuminates our blind areas and increases our self-awareness6. It helps us to identify areas that need improvement that we may otherwise have missed. It can provide valuable information for reflection, feeding in to and complementing the cycle of learning described by Kolb7 (see figure). Today’s environment is in a constant state of change and organisations cannot afford not to be learning8. This requires an outward focus—the rest of the world is an essential learning resource—and a willingness to learn from mistakes9. Feedback, both good and bad, represents valuable external knowledge and a successful organisation will recognise this and be able to assimilate and apply that knowledge10. Organisations that have a strong learning culture accept negative feedback as willingly as they do positive feedback and use it as a source of reflection with a view to improving. In contrast, organisations that deny the validity of negative feedback are unlikely to learn from it and miss a valuable opportunity.

This is not to say that the targets of regulators and inspection bodies are always right. I’ve already noted some of the adverse effects that targets can have on organisational performance. But it would be foolish to throw out the baby with the bathwater. Even amongst a collection of seemingly meaningless targets the feedback about why those targets were missed may provide valuable intelligence that will help improve services further. Even if you don’t believe that what is being measured is useful, this does not mean that there are not valuable lessons that can be learnt from the process. The good organisation will not focus solely on the regulators’ targets—it will have its own more rounded concepts of excellent service delivery, seeing hitting targets as merely a by-product of being good at its core purpose. It will use any and all feedback that it can get to feed into the process of working out how to get better at that purpose.

Of course, getting negative feedback is not easy for employees who have worked hard to deliver a service. It is the job of leaders to maintain morale and to support the staff through this. This is not achieved by being defensive or drawing inwards. In the long term this only means the certainty of disappointing results next time too, and it sets a poor example for individuals’ learning. The leader’s role is to encourage, not stifle, learning11. Leaders need to work to establish a culture of continuous development, to emphasize the positives that can be drawn from learning and to motivate and empower employees to work together to find new solutions12. They should not be making excuses. They should put up their hands and admit the mistakes, and ask how they can do better next time.

- ‘Good’ – but not good enough (2002). Nottingham Evening Post, 12 December, p 20 [↩]

- Francis, R (2013). Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry: executive summary. [Online]. London: The Stationery Office. Available from: http://www.midstaffspublicinquiry.com/sites/default/files/report/Executive%20summary.pdf [Retrieved 23 April 2013] [↩]

- Francis, R (2013). Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry: executive summary. [Online]. London: The Stationery Office. Available from: http://www.midstaffspublicinquiry.com/sites/default/files/report/Executive%20summary.pdf [Retrieved 23 April 2013] [↩]

- Smith, R (2009). NHS targets ‘may have led to 1,200 deaths’ in Mid-Staffordshire. The Telegraph [Online], 17 March. Available from: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/health/healthnews/5008442/NHS-targets-may-have-led-to-1200-deaths-in-Mid-Staffordshire.html [Retrieved 24 April 2013] [↩]

- Kolb, DA (1984). Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall [↩]

- Luft, J (1982). “The Johari Window: a graphic model of awareness in interpersonal relations.” In: Porter, LC and Mohr, B (eds) NTL Reading Book for Human Relations Training [Online]. pp 32–35. Available from: http://www.library.wisc.edu/edvrc/docs/public/pdfs/LIReadings/JohariWindow.pdf [Retrieved 21 April 2013] [↩]

- Kolb, DA (1984). Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall [↩]

- Behn, RD (1998). What right do public managers have to lead? Public Administration Review, 58 (3): 209–224 [↩]

- Davies, HTO and Nutley, SM (2000). Developing learning organisations in the new NHS. British Medical Journal, International edition, 320 (7240): 998–1001 [↩]

- Lane, PJ, Koka, BR and Pathak, S (2006). The reification of absorptive capacity: a critical review and rejuvenation of the construct. The Academy of Management Review, 31 (4): 833–863 [↩]

- Broussine, M (2009). “Public leadership.” In: Bovaird, T and Löffler, E (eds) Public management and governance. 2nd ed [Online]. Abingdon: Routledge. pp 261–277. Available from: MyiLibrary. http://lib.myilibrary.com/Open.aspx?id=197798 [Retrieved 10 October 2012] [↩]

- Heifetz, RA and Laurie, DL (1997). The work of leadership. Harvard Business Review, 75 (1): 124–134 [↩]